Temporal Non-Locality and the Cognitive Perception of Happiness: From the Upanishads to Quantum Theory

Jay Kumar

Department of Religious Studies. Chapman University, Orange, California 92866

Abstract:

The article explores the intriguing relationship between temporal qualia and the cognitive perception of happiness through the modern lens of quantum theory and the science of consciousness, along with their analogues in the ancient Indian monistic traditions of the Upanishads. Specifically, the Upanishads outline a cosmological framework of reality that parallels the fundamental principles of modern quantum theory—one established within temporal non-locality and complementarity. While quantum concepts such as non-locality and complementarity apply to both space and time, this work explores them primarily within a temporal context. The ultimate goal of this work is to demonstrate how certain principles in quantum theory align with philosophical concepts in the Upanishads that propose how consciousness appears to exist in a state of complementarity—simultaneously at the infinite, timeless, non-local level and at the finite, temporally bound, localized realm. The mechanism that accounts for the way the mind conceals the ability to perceive the universe in its fundamental, non-local state is filtration, both quantum and cognitive. Finally, the article offers textual evidence from the Upanishads that state the attainment of happiness begins by first dismantling the cognitive filters that veil reality and create the perceptual illusion of linear and localized time. While the term happiness is both a culturally and socially relative construct and conveys a specific semantic meaning within the western psyche, the same term within the ancient Indian worldview connotes the sense of embodied wholeness and existential completion. Happiness, according to the Upanishads, is a fundamental state of existence that aligns the sacred self with the timeless, infinite dimension of the cosmos. Keywords: complementarity, non-locality, temporal qualia, wave function, consciousness, brain, quantum filtration, cognitive perception, perennial philosophy, Hinduism, Upanishads, Vedanta, happiness, pleasure, atman, Brahman, maya, moksha.

1. Complementarity and Quantum Filtration

“To see a world in a grain of sand and heaven in a wild flower, hold infinity in the palm of your hand and eternity in an hour.” William Blake

There exists a persistent conundrum regarding the human perception of reality, framed within the context that “our sense of reality is different from its mathematical basis as given by physical theories. Although nature at its deepest level is quantum, mechanical and nonlocal, it appears to our minds in everyday experience as local and classical.” (Kak, Chopra & Kafatos, 2014). What, thus, accounts for this disparity in perception that limits human consciousness into constructing reality as localized space-time? Investigation into this phenomenon has only recently been explored by quantum theory and, to some extent, by the science of consciousness. Inquiry into the nature of cognitive perception is, however, not exclusive to the domain of modern science but was once an activity vigorously pursued in the ancient Indian philosophical texts of the Upanishads. One concept that appears to unite the ancient monistic philosophy of the Upanishads and quantum theory is the phenomenon of filtration—cognitive filtration for the Upanishads, quantum filtration for physics.

Quantum filtration, a term more commonly employed in the field of optics, also conveys a feature in quantum mechanics that is “designed to allow the passage of a particular quantum state and no other.” (Roy & Kafatos 1999, p. 664). As will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent sections, the spiritual insights of the Upanishads surmised that the basis of human consciousness is also established in filtration. Specifically, the Upanishads present the view that the mind filters “reality” into a partial, incomplete simulation that we incorrectly identify as an accurate representation of the universe. This process of filtration, both quantum and cognitive, appears to be the reason why consciousness in ordinary everyday experience fails to perceive reality in its non-local, entangled state.

One possible explanation as to why the brain functions in this manner is what Hoffman (2008) refers to as the multimodal user interface (MUI) theory of perception. The theory offers an explanation as to why “perceptual experiences do not match or approximate properties of the objective world, but instead provide a simplified, species-specific, user interface to that world.” (p. 87) In actuality, quantum theory asserts that while reality exists in a non-localized spatiotemporal continuum, certain neural mechanisms may account for the brain operating as an MUI. As a result, human cognition approximates, to the best of its ability, a simulation of reality that perceives time in a localized, finite, fragmented, and linear manner.

The concept of filtration is related to the tenet in quantum mechanics of complementarity and the interpretation of the wave function. Based on Heisenberg’s Uncertainly Principle, it is not possible to determine the exact location of a particle in space-time until it is measured. Rather, a particle only has a probability distribution of its possible position within the wave function. Only when the probability wave of potentiality collapses, does a particle become determined and measured in localized space-time.

This measurable and observable state of a particle that has collapsed from the wave function is known as its eigenstate. Discussing the concept of the eigenstate (or characteristic state) with regard to time, Joseph (2014) argues “Only when the object can be assigned a specific value as to location, or time, or momentum, does it possess an eigenstate, i.e. an eigenstate for position, or an eigenstate for momentum, or an eigenstate for time; each of which is a function of the ‘reduction of the wave function;’ also referred to as wave function collapse.”

As it pertains to the concept of time, a particle within the wave function spans the entire temporal continuum, but only once the collapse of the wave function occurs, will the particle manifest in a specific eigenstate of time, i.e. in a measured and determined point in localized time.

With regard to the concept of complementarity, “Two observables are called complementary when a pure state cannot be a common eigenstate of both observables….Here, we suggest to regard this operational constraint, preventing the simultaneous assessment of two complementary perspectives, being caused by limited resources as in bounded rationality.” (beim Graben & Blutner 2013, p. 1). In essence, conjugate pairs, e.g. wave and particle, operate in mutual exclusivity, yet also are complements to the other in order to describe all phenomenal aspects of reality. Complementarity appears to be a principle that manifests not only at the quantum realm, but one that the spiritual teachings of the Upanishads claim operates equally within the domain of cognition and perception. As Kafatos (2009) argues:

From the early quantum universe, it is likely that quantum-like effects are frozen into the structure of the universe and, therefore, pervasive at all scales in the universe. Complementarity and non-locality are two principles that apply beyond quantum microphysical scales (Kafatos, 1998; 1999) and as such may be considered to be universal foundational principles applying at all scales.

The question again arises why then do quantum phenomena, such as entanglement and non-locality, fail to manifest at the macro-scale level of human perception? The reason again relates to the concept of filtration, specifically the mechanisms of quantum and cognitive filtration that obscure and veil the underlying non-local, entangled character of the universe from everyday consciousness.

2. Temporal Perception and Veiled Non-Locality

“The universe could only come into existence if someone observed it. It does not matter that the observers turned up several billion years later. The universe exists because we are aware of it.” – Martin Rees

Time is a concept that spans the human condition. In examining the human perception of time, Furey and Fortunato (2014) declare, “Psychological research shows that just about all of human experience is dependent upon and influenced by how individuals perceive time, localize themselves consciously within space and time, process their temporally-based perceptions and experiences.” (p. 119). Classical physics has successfully allowed us to calculate and measure time at the macroscale, while relativistic physics demonstrates how time and space are conjugate pairs that manifest in a unified continuum. With the establishment of quantum mechanics, concepts such as entanglement and non-locality allow us to construct a new cosmological model of time that connects with cognitive perception—one that asserts that time is perceived in a complementary timeful and timeless state. In the timeful state, the mind perceives time in its localized, linear, and causal aspects; while in its timeless state as non-local, symmetrical, and entangled. Many of the spiritual traditions throughout history maintain a similar position of human consciousness as having the capacity to abide within these complementary modes of existence. According to quantum theory and the perennial philosophies, the localized qualities of time that exist within the classical realm and that the mind perceives to be real are, in essence, the result of a cognitive distortion.

Joseph (2014) advances how “time, and conceptions about the past, present or future are therefore illusions, as there is no ‘future’ or ‘past’….However, when considered from the perspective of quantum mechanics, timespace is a continuum, a unity, and time does not exist independent of this continuum, except as an act of perceptual registration by consciousness or mechanical means.” The recognition of the mind’s ability to experience both the localized and non-localized complementary aspects of time was the impetus for the ancient Indian mystics to develop advanced mental techniques to master time within the domain of human consciousness. The goal of these disciplines was to liberate from the inherent cognitive filters that limit one’s consciousness into the distorted and fragmented perception of time. One such tactic that facilitated a temporal reframing of reality is kāla-vañcana “time-skewing.” (White 1998, p. 154). A Sanskrit term first encountered in the Tantric traditions of medieval India, kāla-vañcana advances the cognitive ability for humans to transcend the confines of localized space-time and to expand the experience of time from the limited state of timefulness to its underlying state of timelessness.

The mechanism that reduces human consciousness into experiencing time in its temporally localized state is what is referred to as veiled non-locality. The term implies how “consciousness disguises its wholeness and nonlocality in order to produce local processes…. This filtering process allows for specific observations and thoughts in a classical world of everyday experience, while keeping quantum and general relativistic processes out of sight.” (Kak, Chopra & Kafatos 2014).

Having outlined an overview of the quantum principles of filtration, complementarity, and non-locality, it is possible to apply these concepts into exploring the cognitive dimensions of reality and inquiring into the nature of time and consciousness—aspects that have been the foundation for many of the world’s spiritual and mystical traditions. The paper now turns its focus onto one such particular period in history when investigations into the realm of human consciousness became the cornerstone of an entire philosophical and religious movement.

3. The Upanishads

“I go into the Upanishads to ask questions.” Neils Bohr

The ancient philosophers and spiritual adepts of India millennia ago revealed what modern science has only recently affirmed—human perception is capable of experiencing cognitive limitations and creating cognitive illusions. The greatest and most persistent illusion, according to the Indian mystics, was experiencing reality via a cognitive filter of finitude, locality, separation, and duality. One primary aim in life, according to the ancient mystics who composed the Upanishads, was to alter one’s cognitive perspective to perceive reality in its revealed state of transcendence, non-locality, wholeness, and unity.

Spanning a period ca. 800-200 BCE, the Upanishads are a collection of orally composed sacred texts that constitute a highly detailed and complex discussion of philosophy and metaphysics in Indian literature. While the Vedic corpus, texts dating nearly a 1,000 years prior to the Upanishads, explores notions of cosmology, time, and consciousness, the Upanishads usher in the first literary period in India when such concepts were the primary and central theme of investigation. The Upanishads mark the pivotal transition from the earlier ritualism of the Vedic religion to the establishment of core principles evident in Classical Hinduism. In addition to developing tools for psycho-spiritual mastery, concepts such as karma, reincarnation, yoga, and monism, are all witnessed in the Upanishads.

Specifically, with regard to quantum theory I propose that the teachings of the Upanishads can be summarized into centering around three key points:

1) There exists a transcendental, infinite, non-local, dimensionless, unchanging reality that is obscured from the limited cognitive perception of the human senses.

2) This foundational reality is veiled by means of a cognitive illusion that limits consciousness into a localized, linear, and dimensionally finite perception of time.

3) Advanced mental trainings were developed and practiced in order to liberate one’s consciousness from the illusory cognitive limitations of the mind via a perceptual reframing of time into its fundamental non-local, entangled state.

Given the many conceptual parallels between early Indian philosophy and quantum theory, it comes as no surprise that many of the founders of quantum physics, e.g. Bohr, Schrödinger, Heisenberg, were well-versed in, if not heavily influenced by, the sacred wisdom contained within the Upanishads. As Schrödinger famously quotes, “The multiplicity is only apparent. This is the doctrine of the Upanishads. And not of the Upanishads only. The mystical experience of the union with God regularly leads to this view, unless strong prejudices stand in the way.”

The “strong prejudices” to which Schrödinger refers are the cognitive biases and filters upon which we experience reality and frame consciousness. Once this deceptive and limiting cognitive frame of reality (perceived as localized space-time) is followed as the basic nature of existence, it becomes the core, the cause, and the continuity of human suffering. The teachings of the Upanishads state that in order to be liberated from the bonds of ignorance and illusion, one had to identify and dismantle the cognitive barriers that prevented one from achieving a unitive state of consciousness.

The common Western perspective is to view the function of religion primarily to regulate the intimate relationship of humankind with a separately existing cosmic divinity. In the Advaita Vedanta branch of the Hindu traditions, as primarily evident in the Upanishadic texts, they place the individual not apart from the cosmic divine, but co-existent in an integrated relationship within a much greater whole. This notion of unity, interconnectedness, and wholeness among all the constituent parts of the universe, is a cognitive metaphor spanning the multitudinous traditions within the 5,000 years of spiritual, religious, philosophical, and social dimensions of Indian thought (Kumar, 2010).

Underscoring this ancient Indian perspective of humanity abiding in cosmic unity and harmony, Olivelle (2008) posits in his commentary of the Upanishads, “The assumption then is that the universe constitutes a web of relations, that things that appear to stand alone and apart are, in fact, connected in other things. A further assumption is that these real cosmic connections are usually hidden from the view of ordinary people; discovering them constitutes knowledge, knowledge that is secret and is contained in the Upanishads.” (lii).

One such “secret knowledge” advanced in certain texts of the Upanishads is the fundamental concept that the very fabric of the universe is based in consciousness. This concept is outlined in a passage from the Aitareya Upanishad:

4. Ātman and Brahman as Complementary States of Consciousness

“God is the tangential point between zero and infinity.” Alfred Jarry

Perhaps the most transformational and powerful concept that the Upanishads introduce to Indian philosophy and to humanity is the concept of Brahman. Deriving from the Sanskrit verbal root bṛh- “to swell, expand,” the Upanishads depict Brahman as the dimensionless, non-local, transcendent, infinite state of consciousness. While the notion of Brahman resides at the philosophical core of the Upanishads, it has a semantic analogue dating back centuries earlier to the sacred text of the Ṛgveda, in which the Upanishadic notion of Brahman conceptually augments the Sanskrit terms sarva “wholeness” and ṛta “cosmic harmony” evidenced in the earlier Vedic religion (Kumar, 2014).

According to the Upanishads, Brahman has no gender, form, and is imperceptible to the five senses. The only way in which Brahman can be “perceived” is through cognitive awareness, as Brahman Itself is pure consciousness. This goal of the Upanishads, while elegant in its simplicity, was complex in its actualization: to achieve a cognitive state of unity with the transcendental, timeless dimension of reality, Brahman. Drawing a conceptual parallel between Brahman and quantum non-locality, Laszlo (2007) writes:

While Brahman constitutes the dimensionless, non-local state of pure consciousness, it manifests into the localized realm of space-time, as individuated, discrete manifestations of consciousness, known as ātman. While the closest metaphysical analogue of ātman in western thought might be a soul, the Upanishads are clear in stating that the individuated forms of ātman that reside in all living beings are, in actuality, Brahman. Discussing the nature and quality of the ātman, the Katha Upanishad declares, “The knowing Self [ātman] is never born; nor does it die at any time. It has sprung from nothing; nothing has sprung from it. Birthless, eternal, everlasting, and primeval. It is not killed when the body is killed.” (Katha Upanishad I 2,18).

Reflecting upon the inherent qualities of the individuated ātman, the Upanishads, thus, proclaim that it is the essential inner reality within everyone. Furthermore, the great philosophers of the Upanishads arrived at the transformative realization that ātman and Brahman were one and the same.

Within the theoretical framework of quantum mechanics, every single ātman can be conceptualized as a localized, observable, measurable state of the indeterminate, potentiality of Brahman. Furthermore, Brahman and ātman can be viewed as complementary states of consciousness—Brahman being the transcendent, non-local aspect of consciousness and ātman as the immanent, localized aspect of consciousness. Thus, the mystic seers of the Upanishads conceptualized ātman and Brahman as co-existing in a state of spatiotemporal complementarity. While the ātman manifests as an individual consciousness in a specific place and time, it is in essence the complementary counterpart of the timeless and dimensionless Brahman.

It is equally possible to contextualize the concepts of Brahman and ātman within the quantum framework of the wave function. As Joseph (2014) posits, “The wave function is the particle spread out over space and describes all the various possible states of the particle. Likewise, the wave function would describe all the various possible states of time, including past, present, and future.” In the same manner that quantum mechanics regards the wave function as providing a particle with the potentiality to manifest in any possible spatiotemporal, localized state of existence, the Upanishads conjecture that the non-local aspect of Brahman is the unmanifested state of reality that contains the infinite and various possible states of ātman across the space-time continuum. In this manner, Brahman behaves as the quantum wave function, whereas ātman represents the collapsed measurement of the wave function in localized reality.

The goal of the teachings in the Upanishads resides in the conceptualization that the limited and localized consciousness of ātman functions in complementarity with the non- localized, universal consciousness of Brahman. This cognitive awareness leads one to the path of spiritual liberation and everlasting peace. Emphasizing this fundamental truth, the ancient Indian sages encapsulated this concept into key phrases, known as the four māhavākya “great sayings,” that elegantly express the heart of Upanishadic philosophy.

Collectively, these four aphorisms synthesize the core tenet of the Upanishads that can be structured into a simple algebraic equation: A(tman) = B(rahman).

5. Māyā, Moksha, and Cognitive Non-Locality

“I sing the body that is electric! I celebrate the Self yet to be unveiled!” Walt Whitman

It now becomes evident how in general much of “Indian philosophy regards the timeless realm as more real than the manifested realm confined by time and space and says the task of conscious beings is to discover that timelessness and give up any hold it has on the time-space- matter universe.” (Wolf 2004, p. 205). While attaining this cognitive state was achievable, the primary obstacle to experiencing the “timeless realm” where A = B is the cognitive impediment of māyā.

The Sanskrit term māyā developed a multiplicity of meaning within the 4,000 years of Indian literature. In the earliest texts of the Vedic religious corpus, the term conveyed the sense of “magic, art, craft, and power” that explained the numinous qualities of the universe (Mahony 1997, p. 6). In the later monistic philosophy of the Upanishads and the subsequent Advaita Vedānta school, māyā developed the more specialized meaning as “the illusory veil” that envelopes and apportions consciousness into the phenomenological, physical world that parallels Kafatos’ and Kak’s concept of veiled non-locality.

In order to elucidate how the term māyā semantically evolved to convey the concept of illusion, it is important to discuss its etymological roots. The online Monier-Williams Sanskrit- English dictionary identifies numerous meanings for Sanskrit māyā, translations of which include “illusion, unreality, deception, fraud, trickery, sorcery, witchcraft, magic.” Despite the semantic multivalency of the term māyā, its essential meaning can be gleaned by examining the Sanskrit verb from which the word derives. The etymological origin of māyā points back to the Sanskrit verbal root mā- “to measure, limit, apportion, mete out.” Taken in this semantic context, I propose that a more nuanced translation for māyā is conveyed by English limitation.

More precisely, māyā can be contextualized within the framework of Brahman and ātman as a cognitive filtration that limits one’s consciousness from perceiving the fundamental nature of the universe and that filters the undivided, non-local, dimensionless state of potentiality known as Brahman into a limiting, dualistic fragmented vision of reality. The term māyā is semantically connected with Sanskrit avidyā “ignorance”—expressing one’s “ignorance of the unitary character of the ultimate reality” (Jones & Ryan 1997, p. 282) that exists in a state of spatiotemporal non-locality. Thus, māya is a form of existential ignorance that veils the mind from perceiving reality as a non-local, unbounded continuum. As Kak, Chopra, Kafatos, (2014) advance,

As previously outlined, when an individual’s consciousness is established in a cognitive framework where A = B, the Upanishads declare that realization becomes the basis to experience life via truth, knowledge, and, most importantly, the freedom from suffering. However, the primary cause of human suffering is the product of a cognitive state of ignorance and limitation, by which A ≠ B, i.e. a mode of human consciousness grounded in māyā.

Another important philosophical term in the monistic Advaita Vedanta tradition is moksha (mokṣa) “liberation” that derives from the Sanskrit verb muc- “to release, liberate.” In the most literal sense, moksha is the act of releasing oneself from the cycles of death and rebirth within the Classical Indian framework of reincarnation. More precisely, moksha is the vehicle of cognitive liberation from the illusory limitations of māyā that breaks the cycles of human suffering and ignorance, ultimately unifying ātman with Brahman. The following excerpt from the Upanishads reflects this point stating, “By meditating on [Brahman], by striving towards [Brahman], and, further, in the end by becoming the same reality as [Brahman], all illusion disappears. By knowing [Brahman], there is a falling away of all fetters; when the sufferings are destroyed, there is cessation of birth and death.” (Śvetāśvatara Upanishad I, 10-11).

On a side note, the Hindu concept of moksha has a striking religious parallel to the Christian concept of salvation and being freed from sin, as evident in the Biblical terms revelation and apocalypse. In the same manner that the Sanskrit word moksha connotes the “actof liberating oneself from the limited and veiled illusion of reality,” Latin revelatiō and Greek apokalypsis both convey the meaning “to reveal, to unveil” what is hidden and obscured from human perception. While certain Biblical interpretations advocate that humanity suffers due to being born into a state of sin, the Upanishads and later Hindu philosophy advance the view that humans suffer, due to our being born into a cognitive state of māyā. This cognitive limitation binds human consciousness and the ātman into a measured, finite, conditioned perception of space-time as being local and linear.

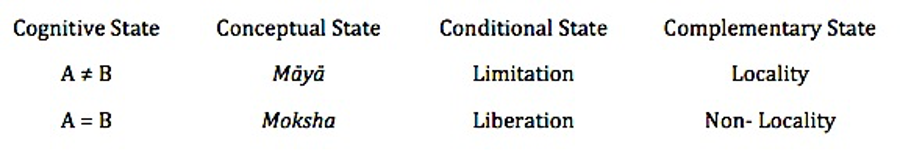

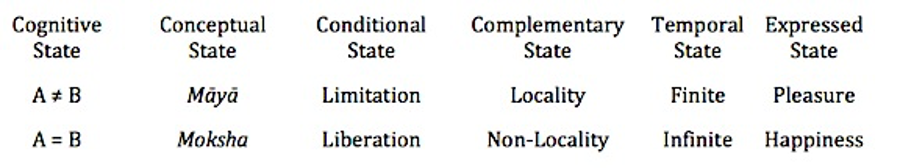

Referring back to the earlier equation, expressing that the goal in the Upanishads is to abide in a cognitive state in which A = B, the concepts of māyā and moksha can be contextualized within quantum theory and summarized in the following manner.

6. Happiness as Temporal Non-Locality

“If you are depressed you are living in the past, if you are anxious you are living in the future, if you are at peace you are living in the present.” Lao Tzu

On the surface, it might appear peculiar for a highly advanced and deeply philosophical system to focus on the nature of happiness. The bias perhaps resides in the semantic expression of the English word happiness. It is predominantly the assumption that in the realm of the western psyche happiness is an emotional state that is finite and fleeting. Contrary to this belief, the philosophers of the Upanishads conceived of happiness not as an emotional, but as an existential, state of awareness and being. A common term found in the Upanishads to convey the concept of happiness is the Sanskrit term sukha. While the word sukha is often translated as happiness, it encompasses a wider semantic sphere that equally connotes the human feeling of “contentment, ease, peace.” According to the Upanishads, embodying a sustained state of sukha was actually an important aim for humans to achieve.

The philosophers of the Upanishads conceived of happiness not as a fleeting state free from emotional or physical pain, but as a sustained state free from psycho-spiritual suffering. The means to achieve this state of inner contentment and equanimity was in dispelling the cognitive limitations of māyā and experiencing the liberated state of moksha. This transformation from māyā to moksha was established in the capacity to shift one’s perception of reality from a local, finite state to a non-local, infinite state of consciousness. It is within this cognitive frame that an ontological perspective of human existence was conceived millennia ago, which conceptually defines happiness in the Upanishads as the absence of existential suffering that results when the mind perceives reality within a state of temporal non-locality.

Furthermore, the ancient sages advanced the point that pleasure was not the same as happiness, as the following passage from the Katha Upanishad suggests: “There is the path of happiness, and there is the path of pleasure. Both attract the soul. Who follows the first comes to good; who follows the path of pleasure fails to reach the end goal. The two paths lie in front of man. Discriminating between them the wise one chooses the path of happiness; the simple- minded takes the path of pleasure.” (Katha Upanishad I 2, 1-2). This differentiation between happiness and pleasure that the Upanishads outline ultimately relates to the concept of human suffering, desires, and wants.

The Upanishads elaborate upon the notion of māyā semantically relating it to the Sanskrit term tṛṣṇā, the “thirsts, cravings, and desires” that result from a life established in the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. The commentaries on the Upanishads further state that a life driven by pleasure sows duḥkha-bīja “the seeds of sorrow” that imprison our consciousness into a temporal state of finitude and an erroneous existential state of separation from Brahman. In this context, the Upanishads posit a clear distinction between a life focused in the aim of pleasure and one in the attainment of happiness. For those following a life of pleasure over that of happiness, the end goal of moksha and the liberation from māyā cannot be attained. The question arises as to what exactly constitutes pleasure versus happiness. The Upanishads advance a unique and powerful notion that the qualitative distinction between pleasure and happiness resides within a temporal context.

To illustrate this point, a well-known story in the Chhāndogya Upanishad has Śvetaketu asking his father about the meaning of life and the attainment of happiness.

When the philosophers of the Upanishads state that “knowledge of the Infinite gives everlasting happiness,” they again refer to happiness being primarily an existential state of perception. A common motif throughout the Upanishads is the recognition that consciousness, space, and time are all multiple concepts that simultaneously express reality. From a temporal perspective, abiding in the limited cognitive state of transience, finitude and locality, i.e. māyā, traps one in an illusory life of pleasure that ultimately leads to suffering. Our consciousness becomes deluded when it is filtered into and imprisoned within the localized, finitude of māyā, preventing one from experiencing ultimate happiness. Once consciousness becomes liberated via a cognitive reframing of reality, one attains moksha. As the Upanishads convey, the moment we perceive reality in its primary non-local, infinite state of unity, the result is happiness.

The Upanishadic philosophers devised many rhetorical arguments to assert that our fundamental essence is happiness. This state of happiness is the result of a cognitive transformation from the delusional limitations of māyā that reinforce our separation from the transcendental consciousness of Brahman. The world of māyā is finite, experienced as temporal locality, and perpetuated by a life pursued by pleasure. In order to experience genuine happiness, one must first abide in a state of mind that equates one’s individuated ātman with Brahman. Another passage further underscores the notion that happiness is an existential state of timeless, unchanging continuity.

The Upanishadic concept of happiness is one that is intimately linked to a state of temporal non- locality. These concepts can now be integrated within a larger framework in the following manner.

7. Conclusion

As Kafatos and Kak exclaim, “If these principles [of neural filtration] did not exist, a very strange, globally-entangled, singularities-rich reality would exist, beyond the limits of any epistemology and ontology that we can imagine and even violating everyday experience. No observations of distinct objects, no scientific theories and, ultimately, no distinct conscious observers, can be conceived in this situation.” (pp. 6-7). The spiritual teachers of the Upanishads were largely disinterested in sacred ritual and practice of divine worship. Among the advancements the Upanishads contributed in the realm of philosophy and metaphysics dating back millennia, the composers of these texts investigated the complex nature of human consciousness. They, furthermore, endeavored to explain the factors that led to and provide the solutions to liberate from the existential suffering perpetuated by māyā. According to the various teachings in the Upanishads, space and time are illusory constructs that skew one’s state of consciousness and limit one’s cognitive perception of reality. The fundamental philosophical motif pervasive in the Upanishads is the advancement that cognitive limitations (māyā) lead to cognitive delusions (suffering).

The psycho-spiritual vehicle of kāla-vañcana expressed that the solution to liberate from suffering resides in skewing one’s temporal perception of reality. This altered state of transformation, known as moksha, occurs upon the revelation that one’s individuated ātman is identical with Brahman. In this way, the core tenets of quantum theory align with the sacred wisdom outlined in the Upanishads—ātman and Brahman are complementary states of consciousness that simultaneously manifest as temporal locality and non-locality.

The Upanishads further sought to explore the correlations between temporal perception and the human quality of sukha, an embodied state of “happiness” expressed by inner contentment, existential peace, and spiritual equanimity. The Sanskrit phrase nālpe sukham asti bhumaiva sukham underscores the notion that “in the finite there is no happiness, only in the infinite is there happiness.” (Chhāndogya Upanishad VII 23) Simply stated, happiness is contingent upon perceiving one’s ātman as either being separate from or united with the transcendent, non-local reality of Brahman. When the mind filters reality through a temporal state of finitude and locality, this becomes the source of our unhappiness. Conversely, when established in a non-local state of unitive consciousness, one experiences a deeply embodied state of sukha, an existential state of happiness that transcends the fleeting feelings of both pleasure and pain.

It is a valid point that the noted 20th century spiritual teacher, Shri Chinmoy, outlines in his commentaries on the Upanishads by elegantly summarizing,

While the science of consciousness and quantum theory are scientific disciplines that have only been recently advanced in the past century, the perennial spiritual wisdom of the Upanishads construct a revolutionary model of reality that views time, consciousness, and the mind as interdependent, co-extensive phenomena. While temporal qualia enable us to experience time in a personally, subjective way, present day models of quantum theory and emerging models of consciousness appear to align with the vastly ancient teachings from the Upanishads to construct a radically innovative conceptualization of time. In this sense, science and spirituality are deeply and powerfully interrelated and complementary worldviews that transcend our perception of time and reveal the nature of reality via a mode of consciousness that is, and will always be, timeless.

REFERENCES

beim Graben, P. and Blutner, R. (2013). Complementarity in cognition entailed by bounded rationality. Talk presented at Fechner Day 2013, October 21 – 25, Freiburg i.Br.

Chopra, D., Kafatos M., Tanzi R. (2011). How consciousness becomes the physical universe. Cosmology, vol. 14. (online) Furey, J. and Fortunato, V. (2014). The Theory of MindTime. Cosmology, vol. 18, 231-245.

Hoffman, D. (2008). Conscious realism and the mind-body problem. Mind & Matter, vol. 6(1), 87-121.

Jones, C. and Ryan, J. (2007). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Facts on File Press.

Joseph, R. (2014) Paradoxes of Time Travel: The Uncertainty Principle, Wave Function, Probability, Entanglement, and Multiple Worlds. Cosmology, vol. 18. 283-302.

Kafatos, M. and Kak, S. (2014). Veiled nonlocality and cosmic censorship (arXiv:1401.2180).

Kak, S., Chopra, D., and Kafatos, M. (2014) Perceived Reality, Quantum Mechanics, and Consciousness. Cosmology, vol. 18. 231-245.

Kumar, J. (2010). Cognitive and Cultural Metaphors of Wholeness in the Ṛgveda. PhD diss., California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, US

Kumar, J. (2014). Ayurveda & early Indian medicine. In: Johnston, L., Bauman, W. (Eds.), Science and Religion: One Planet, Many Possibilities (Routledge Studies in Religion), Routledge Press, Oxford, UK., pp. 174-185.

Laszlo, E. (2007). Science and the Akashic Field. Inner Traditions Press, Rochester, Vermont, US.

Mahony, W. (1997). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY, US

Olivelle, P. (2008). Upaniṣhads (Oxford World’s Classics). Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Roy, S. and Kafatos, M. (1999). Complementarity Principle and Cognition Process. Physics Essays volume 12, number 4, 662-668.

Traunmüller, H. (1998). Measuring time and other spatio-temporal quantities. Apeiron, vol. 5 Nr. 3-4, July-October 1998, 213-218.

White, D. (1998). The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, US.

Wolf, F. A. (2004). The Yoga of Time Travel. Quest Books, Wheaton, IL, US.